Performance

This section will discuss the design, trade-offs, and performance tuning options and recommendations for your ServiceTalk applications.

Design goal

ServiceTalk grew out of the need for a Java networking library with the benefits of async-IO[1] which can hide the complexities of lower level networking libraries such as Netty. We also learned that although asynchronous programming offers scaling benefits it comes with some complexity around control flow, error propagation, debugging, and visibility. In practice there was a desire to mix synchronous (for simplicity and developer velocity) with asynchronous (for improved utilization and vertical scalability) in the same application.

ServiceTalk aims to hit a sweet spot by enabling applications to start simple with a traditional synchronous/blocking programming model and evolve to async-IO as necessary. The value-proposition ServiceTalk offers, is an extensible networking library with out of the box support for commonly used protocols (e.g. HTTP/1.x, HTTP/2.0, etc..) with APIs tailored to each protocol layered in a way to promote evolving programming models (blocking/synchronous → asynchronous) without sacrificing on performance nor forcing you to rewrite your application when you reach the next level of scale.

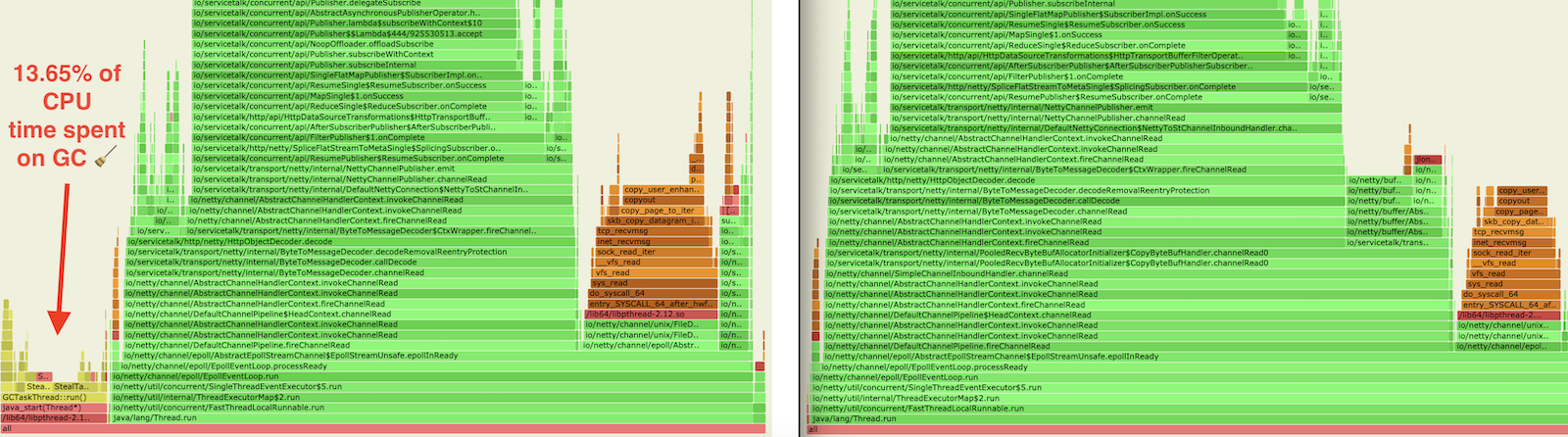

ServiceTalk recognizes the complexities of use (back-pressure, error propagation, RPC, EventLoop threading model, etc…) and duplication (pooling, load balancing, resiliency, request/response correlation, etc…) that comes with Netty. We aim to provide a lightweight networking library, with the best possible performance and minimal overhead in compute and GC pressure over Netty (which is the networking core for many large scale JVM deployments). That said, we may be making performance trade-offs in some areas to favor usability and/or safety. For example more advanced concepts such as Java Memory Model, reference counting, non-blocking and asynchronous control flow.

Trade-offs

As stated in the design goals, ServiceTalk aims to strike a balance between performance and usability, all while being safe out of the box. This section clarifies some aspects, considerations and choices.

Blocking API on top of async

In order to build a library that supports both blocking and asynchronous APIs, we use an asynchronous core and build blocking APIs on top. In case of our blocking APIs, it means there is some overhead involved to orchestrate the hand-off (aka offloading) between EventLoop threads and application worker threads.

Network libraries that dedicate a single thread per connection to do IO and execute user code from that thread may have better throughput and latency as long as the concurrent connection count is low[2]. However there is an inflection point as concurrency increases to vertically scale which may require rewriting the application to take advantage of end-to-end async-IO, or horizontally scale which requires more capital investment. For this reason ServiceTalk may not be optimal in the low concurrency blocking user code scenario, although our benchmarks have shown results within an acceptable threshold for most use cases despite this architecture.

A strategy to avoid the thread hopping is to opt-in to executing user code on the EventLoop thread. However this will have an adverse effect on latency and responsiveness if you execute blocking code. See Evolving to Asynchronous docs for more details.

Reference Counting

At the core of Netty’s Buffer APIs is reference counting which reduces the cost of allocation and collection of direct buffers.

However, it comes with an overhead of managing lifecycle of these reference counted objects. This complexity is passed to the users as they have to explicitly define the lifetime of these objects. ServiceTalk focuses on ease of usage and safety. Manual memory management conflicts with that promise, making ServiceTalk hard to use and potentially unsafe. For this reason in ServiceTalk we’ve decided not to expose reference counted buffers in user facing APIs and deal with this low level complexity internally by copying to heap buffers at the user-facing API boundaries.

This is a conscious decision understanding that this may make some extremely high throughput, low latency use cases almost impossible to implement with ServiceTalk. Benchmarks indicate this is a good trade-off for most use cases and providing safe, easy to use APIs will be a differentiating feature of ServiceTalk. If your benchmarks indicate the lack of reference counting and buffer pooling is the culprit why you cannot meet your performance SLA we suggest users to look into directly building on top of Netty instead.

Reactive core

ServiceTalk’s core design principles aim to enable large scale reactive system. Responsiveness is an essential part of building a reactive system. ServiceTalk implements Reactive Streams APIs to provide flow controlled, responsive networking abstractions. Such flow controlled systems express a well coordinated upper bound on resources (e.g. memory) providing a high level of resiliency in presence of unexpected data spikes.

Concepts such as Future/Promise provide a nice abstraction

for single-item asynchronous operations. Future/Promise implementations (e.g.

CompletableFuture,

CompletionStage)

leverage

function composition to streamline asynchronous control flow

and error propagation. This concept can be extended to multi-item asynchronous operations represented using

Reactive Streams (aka

JDK9 Flow). Such functions on

asynchronous sources are typically referred to as operators in

ServiceTalk. Operators help us transparently propagate demand across business logic thus enabling end-to-end flow

control. This streamlined control flow and end-to-end back-pressure with operators comes with a trade-off which in

practice typically involves additional object allocation and as a side effect may lead to deeper stack traces. In

ServiceTalk we implement our own operators

in order to keep allocation and minimize synchronization while strictly enforcing back-pressure.

We believe that using function composition increases readability for complex asynchronous systems as compared to callbacks, thus following ServiceTalk’s design philosophy of favoring ease of use. However, if your benchmarks indicate operator implementations to be a bottleneck why you cannot meet your SLA please file an issue describing your use case and we will work to improve the operators in question.

Safe-to-block (aka Offloading)

Because ServiceTalk is asynchronous and non-blocking at the core it needs to defend against user or third party code that potentially blocks IO EventLoop threads. Read the chapter on blocking code safe by default for more details.

ServiceTalk has

Executor Affinity which

ensures that the same Executor is used for each Subscriber chain on asynchronous operator boundaries. By default

when using the streaming APIs this requires wrapping on the asynchronous operator boundaries and may result in

additional thread hops between Executors (and even if Executor happens to be the same). Depending upon the use

case, performance costs maybe relatively high but we have the following compensatory strategies in place:

-

ServiceTalk team is investigating ways to reduce the cost of offloading for streaming APIs

-

choosing the appropriate programming model for your use case allows us to be more optimal and reduce offloading

-

you can opt-out of (some or all) offloading via ExecutionStrategy

Tuning options and recommendations

Below sections will offer suggestions that may improve performance depending on your use-case.

Programming model (offloading & flushing)

ServiceTalk offers APIs for various programming paradigms, to allow users to decide which programming model works best for their use case. Different APIs also provide opportunities to optimize the amount of offloading and control when flushing is required. Optimizations related to flushing and offloading can have a non-negligible impact on your application’s performance.

FlushStrategy

Flushing is the act of writing data that is queued in the Netty Channel pipeline to the network socket, typically

via write or

writev

syscall on POSIX operating systems. Syscalls typically involve a user to

kernel-space context-switch which is relatively expensive. To compensate for this Netty introduces and intermediate

write queue to batch write operations triggered by flushing. This reduces the syscall frequency and if done effectively

should not have a negative impact on latency.

For example in benchmarks that involve a small number of writes (e.g. HTTP server responding to a GET request with

in memory content) reducing from 3 flushes to 1 flush almost tripled the throughput of the application. The general rule

of thumb is to try to batch writes as much as possible. We suggest to evaluate this according to your use case, when

data is generated asynchronously (e.g. as a result to a call to another service) you may want to flush more frequently

to avoid introducing latency/responsiveness.

Exposing flush controls on the public API is non-trivial when you have asynchronous control flow. The flush signals must be ordered with respect to the data, and care must be taken not to drop these signals during data transformations. ServiceTalk currently doesn’t expose a way to control flush strategies in the public API but may be able to infer a more optimal strategy if you select the appropriate programming paradigm for the client and service. If you are willing to use an advanced, internal, experimental, subject to change at any time API there is also FlushStrategies that provides control over flushing. Here is a quick summary of this internal API.

| Strategy | Description | Use-case |

|---|---|---|

|

flushes after every item emitted on the write stream of a request/response (eg after the HTTP metadata, after every payload chunk and after HTTP trailers) |

Typically what you want for a streaming application where every write needs to be delivered immediately. |

|

flushes only after the last item emitted on the write stream of a request/response (eg don’t flush until the last HTTP payload chunk or HTTP trailers) |

When your payload is aggregated, you most likely want to perform a single flush of the metadata + payload. |

|

flush after |

This may be interesting if you have a high velocity streaming API, where you don’t necessarily need to emit every item individually and thus can batch a set of writes, with some control over the latency between flushes. |

FlushStrategies and related APIs are experimental and only exposed on the internal API by casting a

ConnectionContext to a NettyConnectionContext on a Connection. For example to update the strategy for an HTTP

client, for a single request one can do:

StreamingHttpClient client = HttpClients.forSingleAddress("localhost", 8080).buildStreaming();

StreamingHttpRequest request = client.post("/foo")

.payloadBody(Publisher.from("first-chunk", "second-chunk"), textSerializer());

// Reserve a connection from the load-balancer to update its strategy prior to requesting

ReservedStreamingHttpConnection connection = client.reserveConnection(request)

.toFuture().get(); // this blocks, for brevity in this example

// Update the strategy to "flush on end"

NettyConnectionContext nettyConnectionCtx = (NettyConnectionContext) connection.connectionContext();

nettyConnectionCtx.updateFlushStrategy((current, isOrig) -> FlushStrategies.flushOnEnd());

StreamingHttpResponse response = connection.request(request);

// consume response.payloadBody()

// Release the connection back to the load-balancer (possibly restore the strategy before returning)

connection.releaseAsync().toFuture().get(); // this blocks, for brevity in this example| `FlushStrategies` and related APIs are advanced, internal, and subject to change. |

On the server side the strategy can be updated as part of the request/response, again by casting the context, or using a

ConnectionAcceptorFilter to set it once for all future requests on the same connection.

HttpServers.forPort(8080)

.appendConnectionAcceptorFilter(delegate -> new ConnectionAcceptor() {

@Override

public Completable accept(final ConnectionContext ctx) {

((NettyConnectionContext)ctx).updateFlushStrategy((current, isOrig) -> FlushStrategies.flushOnEnd());

return delegate.accept(ctx);

}

})

.listenStreamingAndAwait((ctx, request, responseFactory) -> {

((NettyConnectionContext)ctx).updateFlushStrategy((current, isOrig) -> FlushStrategies.flushOnEnd());

return Single.succeeded(responseFactory.ok()

.payloadBody(Publisher.from("first-chunk", "second-chunk"), textSerializer()));

});| `FlushStrategies` and related APIs are advanced, internal, and subject to change. |

ExecutionStrategy (offloading)

ExecutionStrategy is the core abstraction ServiceTalk uses to drive offloading delivering signals and data from the IO EventLoop threads. For HTTP there is HttpExecutionStrategy which adds protocol specific offload points to be used by the clients and services. See Safe to Block for more context into offloading and threading models.

It is possible to override the ExecutionStrategy, but first make sure you are using the appropriate programming

paradigm for client and

service. Depending upon your

protocol it is likely there are higher level constructs such as

routers that provide a per-route API customization (e.g.

JAX-RS via Jersey and

Predicate Router).

If you are using the appropriate programming model,

have reviewed the docs on Evolving to Asynchronous, and

are confident you (or a library you use) will not execute blocking code in control flow in question, then ServiceTalk

allows you to override ExecutionStrategy at multiple levels:

-

Filters implement

HttpExecutionStrategyInfluencer(or similar for your protocol) APIs

| Disabling offloading entirely is an option that gives the best performance when you are 100% sure that none of your code, library code or any ServiceTalk filters [3] that are applied will block. |

Choosing the optimal programming model

Selecting the appropriate programming paradigm can help simplify your application logic (see client programming paradigms and service programming paradigms) and also enable ServiceTalk to apply optimizations behind the scenes (e.g. flushing and offloading). A paradigm is chosen when constructing the client or server, transforming a client on demand on a per-request basis (e.g. HttpClient#asBlockingClient() ), or leveraging a service router’s per-route ability to support the different paradigms. The following table is a summary of how the programming paradigm affects flushing and offloading. Please consider reading the detailed documentation on HTTP Programming models.

| Model | Flush | Offload Server | Offload Client | Use-case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Async Aggregated

|

Single Flush |

Offload handling the request (Meta + payload combined) Offload the response control signals |

Offload handling the response (Meta + payload combined) |

you have aggregated data and your code uses |

Async Streaming

|

Flush Meta |

Offloads receipt of Meta, every payload item and all control signals |

you have streaming data and your code uses |

|

Blocking Aggregated

|

Single Flush |

Offload handling the request (Meta + payload combined) |

None |

you have aggregated data and blocking code |

Blocking Streaming

|

Flush Meta |

Offload receipt of Meta |

Offload control signals |

you have streaming data and blocking code |

This table clarifies how merely choosing the programming model depending on your use-case can improve efficiency. If you can in addition completely opt-out of the offloading (consult with offloading), you will get the best possible performance.

JAX-RS Jersey Router Programming Model

Choosing the right programming model can have significant performance benefits when deploying Jersey routes as well. All Jersey APIs are supported under all models, however there may be some unexpected side-effects, for example when choosing an Aggregated router implementation. You would still be able to use streaming data types [4] as input and output for JAX-RS endpoints, but need to realize that there will be buffering behind the scenes to aggregate and deliver the data in a single payload when the stream completes.

| There is no API-wise need for the Jersey router to be implemented in the 4 different programming models, however it currently offers the most effective way to benefit from these performance optimizations and may improve this in the future. |

| Model | Optimal use-case |

|---|---|

Async Aggregated |

best performance with offloading disabled for aggregated use-cases, optionally using ServiceTalk serializers |

Async Streaming |

best performance with offloading disabled for streaming use-cases, optionally using ServiceTalk serializers. |

Blocking Aggregated |

typical primitive and aggregated JAX-RS data types, best performance in general when endpoints have aggregated data |

Blocking Streaming |

best performance when endpoint depend on |

| When in doubt using Blocking Aggregated or Blocking Streaming is a safe bet to get good performance, especially if you are converting an existing vanilla JAX-RS application. |

If you need to mix Reactive Streams routes with typical JAX-RS Blocking Aggregated routes, you have 2 options.

Either you’ll fall back to the Async Streaming model to avoid aggregating your streams and lose some optimizations for

your Blocking Aggregated routes. Or if your paths allow it, you can front-load your Jersey Router with the ServiceTalk

Predicate Router and compose 2 Jersey routes behind the Predicate Router, each in their respective optimal programming

model.

IO Thread pool sizing

By default ServiceTalk size the IO Thread-pool as follows:

2 * Runtime.getRuntime().availableProcessors()|

Available processors: CPU cores (logical Simultaneous Multithreading (SMT) cores if available) or container compute units as defined by Linux cgroups |

The number of IO threads generally correlates to the number of available processors because this is how much logical

concurrency available to your application. The IO threads are shared across connections and even requests the number of

IO threads is not directly related to the number of requests. If you read and understand the consequences of disabling

offloading then your business logic will execution

directly on an IO thread. As your business logic consumes more processing time (e.g. CPU cycles, blocking calls, etc…)

it may be beneficial to have more than just Runtime.getRuntime().availableProcessors() threads. However the more

processing time you take for a single request/connection, the more latency is incurred by other connections which share

the same IO thread. You should also consider that more threads generally means more context switches. Like anything

performance related your mileage may vary and you should benchmark your specific use case.

In benchmarks which deal in memory data and consume minimal processing time (e.g. HTTP/1.x server responding to GET

request with in memory payload, no compression, encryption, etc…) setting the number of IO threads the equal to number

of logical SMT cores gave the best performance and was ~10% better than 2 * Runtime.getRuntime().availableProcessors()

For example, to override the IO Thread pool on an HTTP client builder (equivalent on the server builder):

IoExecutor ioExecutor = NettyIoExecutors.createIoExecutor(

Runtime.getRuntime().availableProcessors(),

new IoThreadFactory("io-pool"));

HttpClients.forSingleAddress("localhost", 8080)

.ioExecutor(ioExecutor)

.buildStreaming();Socket and Transport Options

ServiceTalk exposes configuration knobs at various layers of the stack. At the lowest layer there are the TCP

SocketOptions and ServiceTalk options, both exposed on the client builder.

BlockingHttpClient client = HttpClients.forSingleAddress("localhost", 8080)

.socketOption(StandardSocketOptions.SO_RCVBUF, 1234567)

.socketOption(StandardSocketOptions.SO_SNDBUF, 1234567)

.socketOption(ServiceTalkSocketOptions.CONNECT_TIMEOUT, 12345)

.socketOption(ServiceTalkSocketOptions.IDLE_TIMEOUT, 12345L)

.socketOption(ServiceTalkSocketOptions.WRITE_BUFFER_THRESHOLD, 12345)

.buildBlocking();

HttpResponse resp = client.request(client.get("/"));HTTP Service auto payload-draining

If a user forgets to consume the request payload (e.g. returns an HTTP 4xx status code and doesn’t care about the

request payload) this may have negative impacts on subsequent requests on the same connection:

-

HTTP/1.x connections may have multiple serial requests and we cannot read the next request until the current request is consumed.

-

HTTP/2.0 connections have flow control on each stream, and we want to consume the payload to return the bytes to flow control

To avoid these issues, ServiceTalk HTTP servers will automatically drain the request payload content after the response is sent. However this adds some additional complexity to the HTTP service control flow in ServiceTalk and adds some overhead. If you know for sure that the payload is always consumed [5], or you are not using the streaming APIs, this mechanism can be disabled to save some CPU and memory as follows:

HttpServers.forPort(8080)

.disableDrainingRequestPayloadBody()

.listenStreamingAndAwait((ctx, request, responseFactory) -> ..);HTTP Header validation

ServiceTalk aims to be safe by default, hence it validates HTTP headers (including cookies) in accordance to the HTTP RFCs. However validation is not for free and comes with some overhead. If you know that your headers will always be valid or are willing to forgo validation, then you can disable header validation as follows:

DefaultHttpHeadersFactory headersFactory = new DefaultHttpHeadersFactory(false /* names */,

false /* cookies */);

HttpClients.forSingleAddress("localhost", 8080)

.protocols(HttpProtocolConfigs.h1().headersFactory(headersFactory).build())

.buildBlocking();AsyncContext

In traditional sequential programming where each request gets its own dedicated thread Java users may rely upon

ThreadLocal to implicitly pass state across API boundaries. This is a convenient feature to take care of cross

cutting concerns that do not have corresponding provisions throughout all layers of APIs (e.g.

MDC, auth, etc…). However when moving to an asynchronous execution model

you are no longer guaranteed to be the sole occupant of a thread over the lifetime of your request/response processing,

and therefore ThreadLocal is not directly usable in the same way. For this reason ServiceTalk offers

AsyncContext which provides a static API similar

to what ThreadLocal provides in one-request-per-thread execution model.

This convenience and safety comes at a performance cost. Intercepting all the code paths in the asynchronous control

flow (e.g. async operators) requires wrapping to save and restore the current context before/after the

asynchronous control flow boundary. In order to provide a static API ThreadLocal is also required, although an

optimization (e.g.

AsyncContextMapHolder

) is used to minimize this cost. This ThreadLocal optimization is enabled by default and can be enabled by using our

DefaultThreadFactory

if you use a custom Executor.

In benchmarks with high throughput and asynchronous operators you will likely see a drop in throughput. Like most common features in ServiceTalk this is enabled by default and can be opted-out of as follows:

Some ServiceTalk features such as OpenTracing may depend on AsyncContext.

|

static {

// place this at the entrypoitn of your application

AsyncContext.disable();

}Netty PooledByteBufAllocator

ServiceTalk leverages Netty’s

PooledByteBufAllocator internally

in cases where we have scope on the

reference counted objects and can ensure they

won’t leak into user code. The PooledByteBufAllocator itself has some configuration options that we currently don’t

expose. There are some internal system properties exposed by Netty which can be used to tweak the default configuration.

Note these are not a public API from ServiceTalk’s perspective and are subject to change at any time. For more info

checkout the jemalloc inspired buffer pool and the

PooledByteBufAllocator source.

Here are a few options for motivation:

| Option | Description | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Number or arenas for HEAP buffers, this impacts how much system memory is reserved for buffer pooling.

|

||

|

Number or arenas for Direct buffers, this impacts how much system memory is reserved for buffer pooling |

netty-tcnative OpenSSL engine

SSL encryption can cause significant compute overhead over non-encrypted traffic. The

SSLEngine for commonly used JDK8

distributions are not known for having the best performance characteristics relative to alternative SSL implementations

available in other languages (e.g. OpenSSL). The

SSLEngine OpenJDK performance has improved

in JDK11 but still may not give comparable performance relative to alternative SSL implementations (e.g. OpenSSL). For

this reason the Netty team created

netty-tcnative

based upon OpenSSL [6] which is a production

ready SSLEngine implementation. Using netty-tcnative with ServiceTalk is as easy as dropping in the

JAR of the SSL implementation on your classpath.

You should also investigate the configuration of SSL which may impact performance. For example selecting the cipher suite and encryption/handshake/ MAC algorithms may have an impact on performance if you are able to hardware acceleration. Performance shouldn’t be the only consideration here as you must consider the security characteristics and what protocols your peers are likely to support (if they are out of your control). It is recommended to consult reputable resources (such as Mozilla Server Side TLS) to learn more.

// add the netty dependency to your build, eg: "io.netty:netty-tcnative-boringssl-static:2.0.25.Final"

BlockingHttpClient client = HttpClients.forSingleAddress("servicetalk.io", 443)

.secure().provider(SecurityConfigurator.SslProvider.OPENSSL).commit()

.buildBlocking();

HttpResponse resp = client.request(client.get("/"));Netty LEAK-detection

ServiceTalk is built on top of Netty. Netty supports

reference counting of ByteBuf objects (reference

counting is not exposed by ServiceTalk). To help

debug reference counting related bugs Netty provides a

leak detector for DirectByteBuffers.

The default SIMPLE detector has a relatively small overhead (intended to be used in production) by sampling a small

subset of buffer allocations and add additional tracking information. This overhead can be avoided at the risk of

less visibility into reference counting bugs as follows:

| This reduces visibility on reference counting bugs in ServiceTalk and Netty. This is not a public API exposed by ServiceTalk and is subject to change at any time. |

-Dio.netty.leakDetection.level=DISABLEDSkip zero initialization for allocated memory

When Java allocates memory it sets all values in the allocated region to 0, according to the JLS, Initial Values of Variables. This ensures you never have to worry about reading uninitialized memory, however in ServiceTalk the allocated memory is wrapped in a Buffer that maintains read and write indices to prevent reading uninitialized memory. Therefore zeroing of `Buffer`s is not necessary and adds considerable overhead while allocating which affects throughput.

ServiceTalk bypasses this zeroing for the default direct BufferAllocator on JDK8. On JDK9+ due to the additional protections put in place, one needs to provide additional system properties to take advantage of this optimization.

To bypass zeroing direct buffers on JDK9+, use:

-Dio.servicetalk.tryReflectionSetAccessible=trueBypassing zeroing for heap buffers works only in JDK9+, to enable it use:

-Dio.netty.tryReflectionSetAccessible=true

--add-exports java.base/jdk.internal.misc=ALL-UNNAMED

These flags do not bypass zeroing when memory is allocated directly through new byte[],

ByteBuffer.allocate(int), or ByteBuffer.allocateDirect(int), this only optimizes the buffers created with the ServiceTalk

BufferAllocators.

|

Internal performance evaluation

While we are careful in not adding unnecessary performance overhead during the development of ServiceTalk, we can’t claim we deliver on this goal unless we measure. Therefore we evaluate ServiceTalk’s performance periodically. The following sections will outline the performance evaluations we do internally. You can use this information to determine whether we have covered the areas of your interest. Every environment and use-case is different which may perform differently and require different tuning strategies, so we would suggest you do your evaluations if performance is critical to your use case.

Test scenarios

We obviously can’t test all scenarios, but our aim is to continuously monitor performance of a set of use cases that are representative of real world use cases while also isolating ServiceTalk as much as possible (e.g. minimize business logic). In addition, we also compare how well other libraries and frameworks in the Java ecosystem perform, for example it’s interesting for us to compare against Netty, as it shows us exactly how much overhead we are adding on top.

Clients and Server types

-

HTTP Clients and Servers in all programming models (see programming models for performance implications)

-

Async Aggregated

-

Async Streaming

-

Blocking Aggregated

-

Blocking Streaming

-

-

JAX-RS Jersey router performance

-

common JAX-RS data types (

String,byte[],InputStream,OutputStream) -

Reactive Streams types (

Single<T>,Publisher<T>,Publisher<Buffer>) -

JSON with Jersey Jackson module &

ServiceTalkJersey Jackson module

Features and dimensions

-

PLAIN vs SSL

-

offloading (default) vs not-offloading

-

HTTP Methods

-

GET

-

POST

-

-

Payload sizes

-

0

-

256

-

16KB

-

256KB

-

-

AsyncContext enable/disable

-

Header validation enable/disable

-

IO Thread count

-

Connection count

Conclusion

These test scenarios and benchmarks have helped us convince ourselves that ServiceTalk performs as expected compared to other libraries in the industry for the use cases that interests us. We are interested in improving ServiceTalk in general and would add more benchmarks as necessary.

request.payloadBodyAndTrailers().ignoreElements()